さきほどTBSラジオからハワイで行われたクリントン-岡田会談に関してコメントを求められました。また5分程度だったんで思うように喋られず。早口になっちゃうんですよね。ダメポです。

というか、こちらはいまハイチの地震報道一色で外相会談に関してなんらテレビでは速報も続報もありません。新聞がかろうじてAPやロイター電を伝えているのですが、ワシントンポストがかなり今回の雰囲気の変わり具合を如実にというか、なんとなく描写していて面白いです。そこには、日米関係に詳しい人たちが「たかだか40機のヘリコプターの移設問題くらいで日米関係をハイジャックさせてはいけない」って言っている、って書いているのです。NYタイムズもまた、今回の会談を日本との関係を修復するためのものだと位置づけていたし、あらら、なんだか日本で伝えられているのとは違う感じです。(って、私は前から言っていたんですけどね)。

日本の報道をオンラインでチェックしてみたら、「普天間、平行線」という見出し。でもそれって「5月までに決める=5月までは決めない」ってことだからすでにわかってることで、いまのこの時点で見出しになるようなことではないはずです。ことさら日米の「亀裂」を取り上げてみて、この人たちは何が言いたいのか? というかどこに着目しているのか?

アメリカの新聞もかねてから普天間および沖縄にはかなり同情的な視線を持っていたのでしたが、今回はややそれとも報道の仕方が違うようです。より積極的に、日米の不協和音を鎮めるようなトーンが目立って、NYタイムズは「普天間という個別問題で日米同盟という大きな枠組みは壊れない(indestructible)のだ」ってクリントン国務長官が言ってることを取り上げています。

もちろん米国は「これまでの日米同盟こそがベストの道」という主張を崩してはいません。しかしそれはどういうことかというと、意地悪い言い方ですけど、これから20年先を見越した東アジアの安全保障のためにベストという意味じゃなくて、とりあえず今年のいまの時点のオバマ政権にとって一番いい、という意味なんですよね。というのもいまオバマ政権は内憂外患というか、支持率、昨日の NBCの調査で50%を初めて切って、46%になっちゃったんです。アフガン戦争の行方が見えないこと、失業率が10%を超えたままであること、税金を投入して救った金融業界へのボーナスがまた平均で5千万円だとかいうニュースが出始めて、国民の不満がたまりにたまっている。そういう大わらわなときに、これまでいつも助けてくれていた日本までが面倒臭いことを言い始めて、とことん困っているんです。ここはどうあっても、合意どおりに進めてほしい、それがベストな道なのだっていわざるを得ないでしょう。

で、そうしたうえでで、新聞の見出しはクリントン国務長官が日本の決定の遅れをアクセプトした、受け入れた、というトーンになっているのです。

じつはこれには伏線があります。1月6日のNYタイムズに、ジョセフ・ナイが、この人はハーバード大の名誉教授でリベラル派の国際学者といわれてる人で、民主党のカーターやクリントン政権で外交や軍事政策に関わった専門家でもあるんですが、この重鎮が、普天間移設問題に関して寄稿して「some in Washington want to play hardball with the new Japanese government. But that would be unwise(ワシントンの一部には、日本の新政権に対して強硬な姿勢をとりたがっている連中がいるけれども、そりゃバカだ)」といって、「忍耐強く交渉にあたるよう求めた」(朝日新聞)のです。

これを報じた朝日新聞を引きましょう。

同紙は「ナイ氏は『個別の問題よりも大きな同盟』と題する論文で、『我々には、もっと忍耐づよく、戦略的な交渉が必要だ。(普天間のような)二次的な問題のせいで、東アジアの長期的な戦略を脅かしてしまっている』とした。

東アジアの安全を守る最善の方法は、『日本の手厚い支援に支えられた米軍駐留の維持』だと強調」した、というわけです。

まあ、「論文」というか、全体で750語ほどの新聞用の短い寄稿文なんですが、これとまったくおなじ文脈でクリントンが今回の岡田会談に臨んだように見受けられます。「中国の軍事的な台頭を考慮して」という部分ももちろん共有しています。

ナイはじつはクリントンの外交上の知恵袋でもあって、一時は駐日大使になるかとも思われた人なんですけど、結局はオバマの選挙スポンサーだったルースが大使になったという経緯があります。で、そのオバマがナイを嫌った理由の1つが、ナイってのがかなりこれが戦略的な人でして、これも日本の事情を慮ってというよりはアメリカの国益がどうか、東アジアのアメリカの覇権をどうするか、という(まあ、もっともな)立場なんですね。末尾にこの寄稿文全体を貼付けておきますが、この中で朝日が触れていないニュアンスとしてかれはこう言っています。

**

Even if Mr. Hatoyama eventually gives in on the base plan, we need a more patient and strategic approach to Japan. We are allowing a second-order issue to threaten our long-term strategy for East Asia. Futenma, it is worth noting, is not the only matter that the new government has raised. It also speaks of wanting a more equal alliance and better relations with China, and of creating an East Asian community — though it is far from clear what any of this means.

たとえ鳩山氏が結果的に基地計画で折れたとしても、われわれは日本に対してより我慢強く戦略的なアプローチをしていかねばならない。われわれがいまやっていることは東アジアのためのわれわれの長期的戦略を二次的な問題で脅かしているという事態なのである。普天間は、そんなものは屁みたいなもんだし、日本の新政権が持ち出してきた数多くの問題の1つでしかない。新政権が言っているのはより平等な同盟関係とか、中国とのよりよい関係とか、東アジアのコミュニティの創造だとか、まあ、意味ははっきりとはわからないまでもそういうことなのだ。

When I helped to develop the Pentagon’s East Asian Strategy Report in 1995, we started with the reality that there were three major powers in the region — the United States, Japan and China — and that maintaining our alliance with Japan would shape the environment into which China was emerging. We wanted to integrate China into the international system by, say, inviting it to join the World Trade Organization, but we needed to hedge against the danger that a future and stronger China might turn aggressive.

東アジア戦略に関して1995年にペンタゴンの報告書を手伝ったときに、われわれの見据えたことはこの地域に3つの大国が存在しているという現実だった。すなわち、米国、日本、中国である。われわれが日本との同盟関係を維持することが中国が台頭してくるその環境を決定づけるのである。われわれは中国が国際的なシステムの中に入ってくるよう望んでいた。たとえば世界貿易機関(WTO)に参加するなどして。しかしわれわれは同時に未来のより強大になった中国が好戦的に変わる危険にも備えなくてはならなかったのだ。

**

かなりしたたかでしょう。

そう、日本が中国を見ているように、アメリカもまた中国との関係で日本はとても重要な国なのです。その三つ巴の(?)バランスを上手く保たねば、この地域でのアメリカの覇権も危うい。そのためには普天間など取るに足らない問題だ、というわけです。おそらくこれはクリントン国務省の考え方と同じと考えてよい。

ワシントンポストはまさにそこを次のように書いています。(翻訳文のカッコ内は私の註です)

The new tone also stems from a growing realization in Washington and Tokyo that the base issue cannot be allowed to dominate an alliance crucial to both countries at a time when a resurgent China is remaking Asia, signing trade deals and staking claims to ocean resources.

ワシントンと東京で、再び台頭してきた中国がアジアを再構築し貿易問題をまとめ海洋資源の所有権を主張しようとしているとき、米日両国にとって死活の問題である同盟関係を基地問題などで右往左往させてはならないという認識が育ってきて、(日米間の亀裂、不協和音とは違う)あらたな傾向が出てきた。

(中略)

But Tuesday, Clinton was understanding.

火曜日(12日=日米外相会談の日)、クリントンは(日本の立場を)理解していた。

"We are respectful of the process that the Japanese government is going through," she said. "We also have an appreciation for some of the difficult new issues that this government must address," including the widespread opposition to the U.S. military presence on Okinawa.

「日本政府が経験している過程はわれわれも尊重している」と彼女(クリントン)は言った。「またこの(日本の)政府が困難で新たな問題のいくつかに取り組んでいることも私たちは評価している」と。その問題には沖縄の米軍の駐留に対する広い反対意見のことも含まれている。

**

ね、いかに「普天間、平行線」という見出しが間違っているか、これでわかるでしょ?

岡田外相と、その報告を受けた鳩山首相が上機嫌そうだったのは、こういうことなのです。

*****

以下、ナイのエッセーを添付しときます。時間があったら翻訳しますけど、いまはちょっと全部は無理。

SEEN from Tokyo, America’s relationship with Japan faces a crisis. The immediate problem is deadlock over a plan to move an American military base on the island of Okinawa. It sounds simple, but this is an issue with a long back story that could create a serious rift with one of our most crucial allies.

When I was in the Pentagon more than a decade ago, we began planning to reduce the burden that our presence places on Okinawa, which houses more than half of the 47,000 American troops in Japan. The Marine Corps Air Station Futenma was a particular problem because of its proximity to a crowded city, Ginowan. After years of negotiation, the Japanese and American governments agreed in 2006 to move the base to a less populated part of Okinawa and to move 8,000 Marines from Okinawa to Guam by 2014.

The plan was thrown into jeopardy last summer when the Japanese voted out the Liberal Democratic Party that had governed the country for nearly half a century in favor of the Democratic Party of Japan. The new prime minister, Yukio Hatoyama, leads a government that is inexperienced, divided and still in the thrall of campaign promises to move the base off the island or out of Japan completely.

The Pentagon is properly annoyed that Mr. Hatoyama is trying to go back on an agreement that took more than a decade to work out and that has major implications for the Marine Corps’ budget and force realignment. Secretary of Defense Robert Gates expressed displeasure during a trip to Japan in October, calling any reassessment of the plan “counterproductive.” When he visited Tokyo in November, President Obama agreed to a high-level working group to consider the Futenma question. But since then, Mr. Hatoyama has said he will delay a final decision on relocation until at least May.

Not surprisingly, some in Washington want to play hardball with the new Japanese government. But that would be unwise, for Mr. Hatoyama is caught in a vise, with the Americans squeezing from one side and a small left-wing party (upon which his majority in the upper house of the legislature depends) threatening to quit the coalition if he makes any significant concessions to the Americans. Further complicating matters, the future of Futenma is deeply contentious for Okinawans.

Even if Mr. Hatoyama eventually gives in on the base plan, we need a more patient and strategic approach to Japan. We are allowing a second-order issue to threaten our long-term strategy for East Asia. Futenma, it is worth noting, is not the only matter that the new government has raised. It also speaks of wanting a more equal alliance and better relations with China, and of creating an East Asian community — though it is far from clear what any of this means.

When I helped to develop the Pentagon’s East Asian Strategy Report in 1995, we started with the reality that there were three major powers in the region — the United States, Japan and China — and that maintaining our alliance with Japan would shape the environment into which China was emerging. We wanted to integrate China into the international system by, say, inviting it to join the World Trade Organization, but we needed to hedge against the danger that a future and stronger China might turn aggressive.

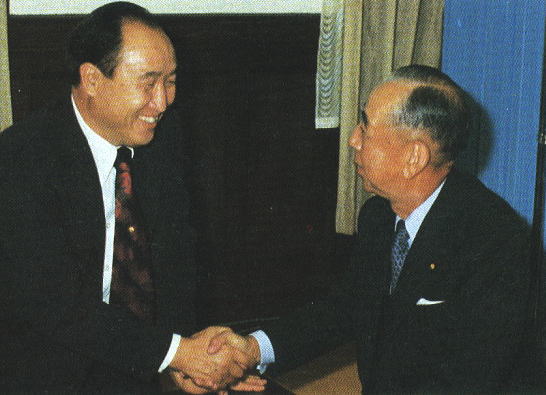

After a year and a half of extensive negotiations, the United States and Japan agreed that our alliance, rather than representing a cold war relic, was the basis for stability and prosperity in the region. President Bill Clinton and Prime Minister Ryutaro Hashimoto affirmed that in their 1996 Tokyo declaration. This strategy of “integrate, but hedge” continued to guide American foreign policy through the years of the Bush administration.

This year is the 50th anniversary of the United States-Japan security treaty. The two countries will miss a major opportunity if they let the base controversy lead to bitter feelings or the further reduction of American forces in Japan. The best guarantee of security in a region where China remains a long-term challenge and a nuclear North Korea poses a clear threat remains the presence of American troops, which Japan helps to maintain with generous host nation support.

Sometimes Japanese officials quietly welcome “gaiatsu,” or foreign pressure, to help resolve their own bureaucratic deadlocks. But that is not the case here: if the United States undercuts the new Japanese government and creates resentment among the Japanese public, then a victory on Futenma could prove Pyrrhic.